Never Sleeping

By Daniel Felsenfeld, special to The Sybaritic Singer

‘If I sleep, who’ll give me the moon?’ —Albert Camus, Caligula (Stuart Gilbert, trans.)

Sleep eludes me, has for the entirety of my conscious life. When a child, the flashlight beneath the covers; as a younger adult, crossword puzzles, more books, and work (of the creative and tedious varieties); as an older person, television, surfing, unfortunate and potentially ruinous encounters with online booksellers, and, especially these days, unabashed fretting. Night has always been—or at least felt like—my domain, much more than some, and for good or ill this has shaped my psyche as much as (if not more that) just about everything.

In two instances I have made attempts to translate my nocturnal peregrinations into music: the overstuffed study in agitation Insomnia Redux; 4am—which began life as a solo piano piece eventually translated into iterations for orchestra and Pierrot Ensemble—and the much smaller, more plangent From Sleepless Nights (a setting of a passage from Elizabeth Hardwick’s astonishing autobiographical cri-de-coeur Sleepless Nights). In both instances, when I mentioned in program notes or preconcert lectures my own insomnia as part of the impetus for the work, post-concert chats revolved not around the music but more the affliction, or as better put, a mental illness—one of the “cool” mental illnesses, it seems. Over innumerable plastic cups of post-concert wine I’ve had oddly personal conversations about my sleeplessness with perfect strangers (“Wow, you have that much trouble? I just fall asleep as soon as my head hits the pillow,” which has always been akin, in my mind, to telling an asthmatic that “I just breathe all the time, no sweat.”). And yet, as uncomfortable as these conversations can be, I continue to welcome the chance to explore sleep as an option, because, like so many of the big topic (i.e. love, sex, death, beauty), it is a bottomless well of possibilities.

The Moondrunk State

As a composer (which to me means a deep listener to the music of better composers than myself), I sought music about the moondrunk state, the wild post-midnight activity which is next-to-impossible to capture (Elliott Carter’s big song cycles In Sleep, In Thunder and A Mirror on Which to Dwell turned me on as a student, especially as 1) the latter features a song called “Insomnia” and 2) apparently this composer was a fellow sufferer, something we discussed too-briefly the one time I had the privilege of meeting him). Chopin wrote Nocturnes, as did I (I failed), and there were pieces and songs that addressed these matters—Carter’s Night Fantasy did not, in my estimation, live up to the title’s promise, and even on the pop side night songs like Iggy Pop’s “Nightclubbing,” Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne,” and even much of the music that defined my favorite nocturne Twin Peaks failed to meet my own need. But quite honestly, what could? I held night in such high regard that inevitably nothing was going to be able to meet my exacting standards.

So instead I pursued the moon.

How much excellent music has been made of and/or by moonfall? From Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire to the song “Mooonfall” from The Mystery of Edwin Drood, to, yes, the “Moonlight” Sonata, the moon rates. Even more than sunrise, it is beneath the moon that so much takes place, from transgression to penitence, from torpor to resolve, from terror to assignation. But like “night” (the title, incidentally, of the recorded collaboration between pianist Simone Dinnerstein and singer-songwriter Tift Merritt, on which my piece The Cohen Variations appears)

The Nocturnal Dance Party

It stands to reason that my daughter, now six years old, made her primordial indication she would enter the world under cover of night; it stands even more clearly to reason that she, like her father, has, to say the least, a complicated relationship with sleep. While other households have children asleep just post-sundown, our daughter, herself a sorceress of sorts, often begin the dance party long past dark, and takes pride (to her parents’ collective admiring chagrin) in being, in her words, a “midnight girl.”

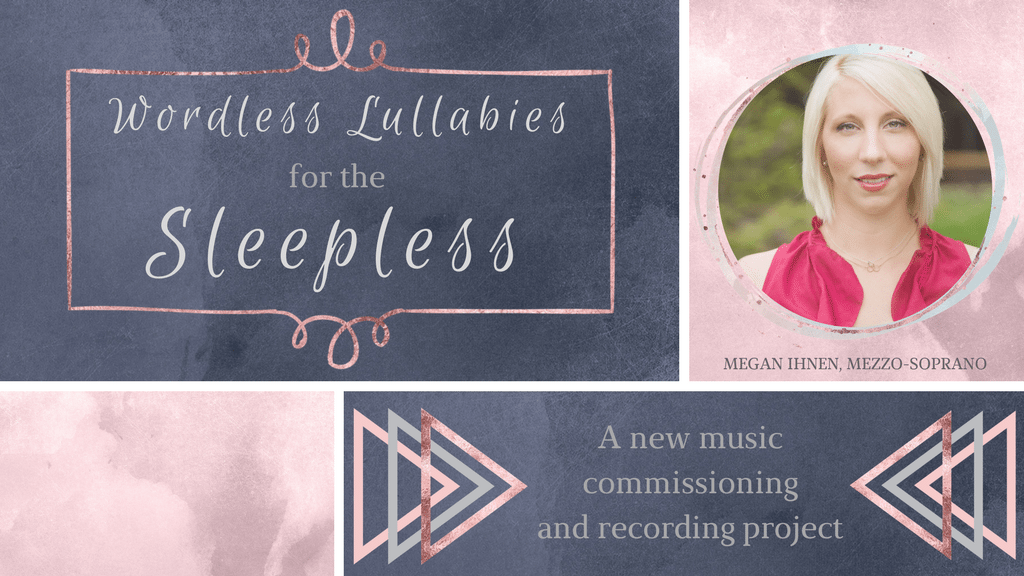

All of this is why, when the amazing mezzo-soprano-cum-force-of-nature Megan Ihnen (whose blog I am currently occupying and hoping not to have lessened the quality of in a permanent way) proposed a wordless lullaby project I leapt, because lullabies—those often-saccharine tunes one sings to unwittingly pass a child from your arms to those of Mr. Morpheus—have always been tricky and troubling, and, being a composer, I prefer to work out problems in musical form. The project also hits a combination of so many of my own personal interests—sleep, lunar cycles, darkness, parenting, things done and said in secret, safety versus exposure, terror and calm, not to mention writing for the voice—that I could not help but want to be part of it. After all, how many lullabies had I created in nightly, often vain, attempts to wrestle Clara down; and once I had, how many thousands of times had I looked in on her once down to make sure she persisted in breathing? Sleep and it’s coaxing, like all the “big” topics, is never simple, always personal, and often a source of more fear and anxiousness belied by the frequent “nursery rhyme” mode in which it is presented.

On The Subject of Lullabies…

This project also hits one absolutely huge point with which I have been struggling, and that is the idea that children need only the simplest, easiest, and calmest material. As a parent I have found the opposite to be true: that darkness and complexity can soothe a dark and complex mind, and that both absolutes and grotesques can inform—and that it is appropriate to be afraid of the dark, and that the real dream-the-impossible-dream achievement to unlock is offering the very important tools—music, especially music from a human voice, and especially from a nuanced and beautiful human voice, being chief among them—to light their (our) way.

Composer Daniel Felsenfeld (b.1970) has been commissioned and performed by Simone Dinnerstein, Opera On Tap, the Chorus of Trinity Wall Street, Metropolis Ensemble, Meerenai Shim, Two Sense (Lisa Moore and Ashley Bathgate), ASCAP, San Jose Opera, ETHEL, Great Noise Ensemble, American Opera Projects, the Da Capo Chamber Players, Transit, Redshift, Nadia Sirota, Blair McMillen, Two Sides Sounding, Parhelion Trio, Alcyone Ensemble, Friction Quartet, Kristin Elgersma, Eleanor Taylor and Jen Devore, Holly Chatham, Momenta Quartet, Nouvelle Ensemble Moderne, Cornelius Duffallo, Stephianie Mortimore, Mellissa Hughes, Corey Dargel, Jenny Lin, New York City Opera (VOX), ACME, Redshift, New Gallery Consert Series, Gabriella Diaz, Sarah Bob, Jody Redhage, Caroline Worra, New England Conservatory Philharmonic in venues such as Carnegie Hall, Galapagos Art Space, The Kimmell Center, Jordan Hall, the Kitchen, Miller Theatre, Stanford University, Harvard University, The Stone, Brown University, Le Poisson Rouge, City Winery, and the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. as part of the BEAT Festival, MATA Festival, Make Music New York, 21c Liederabend, Opera Grows in Brooklyn, New Brew, Serial Underground, and John Wesley Harding’s Cabinet of Wonders. Future projects include pieces for Sequitur (based on unpublished writings of David Foster Wallace), an opera based on the life of Dr. Kinsey for Opera on Tap, Kathy Supove, Michael Zegarski, Great Noise, Ashley Bathgate and Ensemble 212, Vocallective, Cadillac Moon Ensemble and Vision Into Art.

“IF I SLEEP, WHO’LL GIVE ME THE MOON?” A quote that resonated so much with me and I’m sure I’ll keep forever. This is such great writing (despite me not fully understanding all the musical terms. Great post

Hi Vivian,

Thank you so much for checking it out! I appreciate you leaving a comment too!

wow – at first I thought this didn’t apply to me – I thought of sleep as easy to come by, but on further reflection realize I rise many times during the night (for various reasons)- never having quite grasped the significance of the night time “moon” hours, although the songs live within (Moon River, Moonlight Sonata, Fly Me to the Moon, among my favorites) – Training in therapeutic music for transition and healing has put me in touch with traditional and not so traditional “lullabies”. I look forward to hearing the end results of this project of wordless lullabies – so much healing can be carried in just the music alone…

Hi Donna,

Yes, you bring up such a good point! Even if we’re not sleepless, we can still have a lot of healing during that time of the evening/night with music.