What do you think of when you think of autism?

For many people, the first thought is of aloof, broken, emotionless individuals – perhaps with a side serving of savant skills. It’s a stereotype that’s been reinforced in many a media depiction, with Rain Man especially significant in contributing to the general public perception; by 2007, The Big Bang Theory didn’t even need to bother explicitly calling Sheldon Cooper autistic, his collection of stereotypical traits could just be left unlabelled and still recognised accordingly for better and worse. Autism, however, is a spectrum condition, so it can manifest itself in a variety of ways.

Sensory Hypersensitivity

For many autistic people, myself very much included, the biggest difficulties can stem from sensory hypersensitivity. The National Autistic Society, the UK’s largest charity for autistic people and their families, produced a video last year that vividly illustrates what it can feel like to be overly sensitive to sensory input. (As such, a warning that it contains some flashing lights and sudden loud noises which could affect some people who watch it.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lr4_dOorquQ

I watched it in the process of writing this post. I just about made it to the end, and then hurried away from the screen, had a little cry – some autistic people get emotionally overwhelmed at the slightest provocation, an utter mismatch between stereotype and reality – and listened to soothing music. Soft, controlled sensory input is something I find immensely valuable.

Autism and Sleep Disorders

This goes double at night. Autistic people are disproportionately likely to have some form of sleep disorder – in fact, some estimates place the incidence as high as 80%. And when I’m in “bat mode,” as I jokingly refer to my night wakefulness – especially as it’s paired with hearing too much, liking the dark, and occasionally writing for coloratura soprano – I need to be calmed. I need to block out the sound of the radiator pumping hot water around the house, or the occasional roar of a passing train from a railway track that’s not even particularly close by, because to my ears those are not quiet sounds.

https://twitter.com/pickleshy/status/839009378292281345

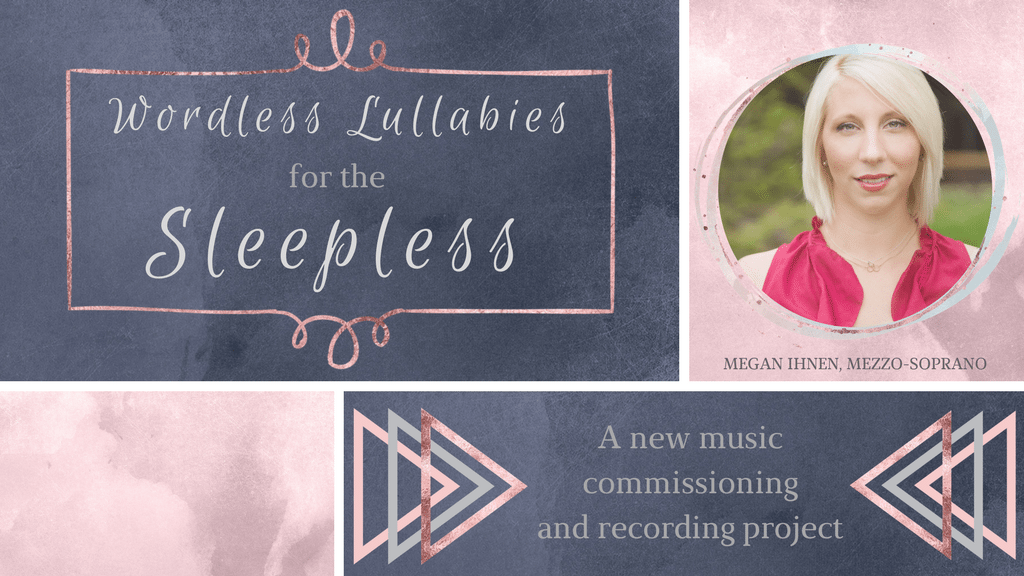

Imagine my delight when I saw a vague suggestion on Twitter that wordless lullabies for the sleepless as sung by Megan should be a thing. On one level, it is perfect for me because of that intense personal connection to the concept of vocal music designed specifically to soothe, to calm, to wipe away or block out the unwanted feelings that surface all too easily in the dark. On the other, it happens to suit the skills I have… and work around the gaps in that skill set.

A Perfectly Suited Project

I’m just a hobbyist composer, and on some level I’m wary of calling myself even that; I didn’t have a musical childhood, never learned an instrument to any meaningful standard, stopped music lessons in school as soon as the option became available at the age of 14 under the British school system, and don’t trust myself writing for instruments at all. (There are very good orchestral composers out there who should have the same sort of attitude to vocal writing, but don’t. Remembering this helps me feel less of an imposter.)

What I do have going for me, conversely: instinctive melody-writing abilities I’ve had affirmed by too many professional musicians to keep undermining them; an ability to couple this with creation of my own text for singing; and a fascination with the human voice in all its variety with an accompanying desire to want to showcase it in its most flattering guise, whatever that may mean for each individual.

Naturally Sybaritic

As an autistic person trying to survive in an overstimulating world, I almost can’t not be in some sense sybaritic – sources of “sensuous luxury or pleasure” can be my survival kit, the smoothing paper filing away the painful sharp edges around me. It is my immense pleasure to be in a position to help provide not only myself, but others as well, a source of sensuous luxury or pleasure, by way of giving Megan instructions on how to create it. (For, make no mistake, it is her instrument, and specifically its gloriously appealing timbre, that will be what brings the comfort and joy…)

In fact, I believe in general that new music should be willing to change tack along this kind of direction; confront and challenge a little less, comfort and console a little more. There is now a wealth of dizzyingly intellectual new material being composed – much of it fascinating, some of it wonderful – and that boundary-pushing is a rightful place for new music. Yet there is – or at least should be – room for new simple pleasures, more accessible to listeners and/or singers, that can be appreciated not as wonders of creativity and/or technique but simply as pleasing for what they are. There’s certainly a place for that in the earspace of this autistic listener – and the wordless nature of the lullaby project is of particular appeal to the many autistic people whose auditory processing difficulties make it difficult or impossible to decipher what is actually being sung beneath the layers of resonance that underpin the sound of a classically-trained voice.

World Autism Awareness Week

On that note, I write this during World Autism Awareness Week, and now it is April and it is “Autism Awareness Month” as declared by the insidious Autism Speaks, a charity hated by most actually autistic people because of their emphasis on curing autism and spinning a narrative of us as helpless and damaging. (Autistic-run groups such as the Autistic Self Advocacy Network offer a quite different perspective, and while the National Autistic Society is not run by autistic people it is broadly respected by them.) I’d like to think that I can bring awareness that autistic people aren’t all like that, or like Sheldon Cooper for that matter. Some of us are less interested in talking about programming threads, and more interested in weaving melodic threads.

David Howell is a 30-year-old autistic man from the UK, currently in the process of gaining certification as a personal trainer. A graduate in Economics and Politics at the internationally regarded University of Southampton, David worked for the Office for National Statistics, the UK’s national statistical agency, before leaving to pursue his ambition as a Health at Every Size (HAES) fitness professional. He also writes vocal music, including accompanying text; he is currently working with singers including Kim Feltkamp, Katherine Bruton, and Lisa Neher.