What makes for a truly modern opera production? Washington National Opera‘s current production of composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer‘s Moby-Dick is a model example. A feast for the ears as well as the eyes, Moby-Dick is awash in innovative performance and design. Although the search for the great white whale is drenched in ego, the production was committed to effective storytelling. This production is the culmination of the winter season devoted to new American music at the Washington National Opera. Francesca Zambello, Artistic Director, wrote in her program note, “I look at it this way: opera may have originated in Italy, but I’d like to see us get to a point where Americans make and consumer it as enthusiastically as they do pizza – another Italian import many of us happen to enjoy.” With this incredible work, the Washington National Opera is doing its part to hasten the ascendancy of powerful, visible American opera.

Ahab’s quest for Moby Dick is grand, ungodly, and all-consuming. He is a charismatic leader who persuades an entire ship of whalers to forgo hunting for months on end just to find the one creature of his obsession. With a character this terrific, the voice must be almost superhuman. Washington National found the right man with American tenor Carl Tanner. Heggie’s score has moments of quiet introspection but more often than not there is an absolute tidal wave of sound pouring from the stage and orchestra pit. Tanner demonstrated impressive command of his heldentenor vocal abilities and physical presence – always carrying over the full-throttle texture even while covering the raked stage on a peg leg. However, it was one of the tender moments that commanded all attention. The duet in Act II – Day Four: the next morning between Tanner as Ahab and American baritone Matthew Worth as Starbuck was marked with longing and a perfect vocal dichotomy between the worn, compulsive captain and the resolute first mate. Worth also impressed with vocal warmth and elongation of tension during the scene in Ahab’s cabin when he considers shooting the captain to gain his freedom to see his wife and child again.

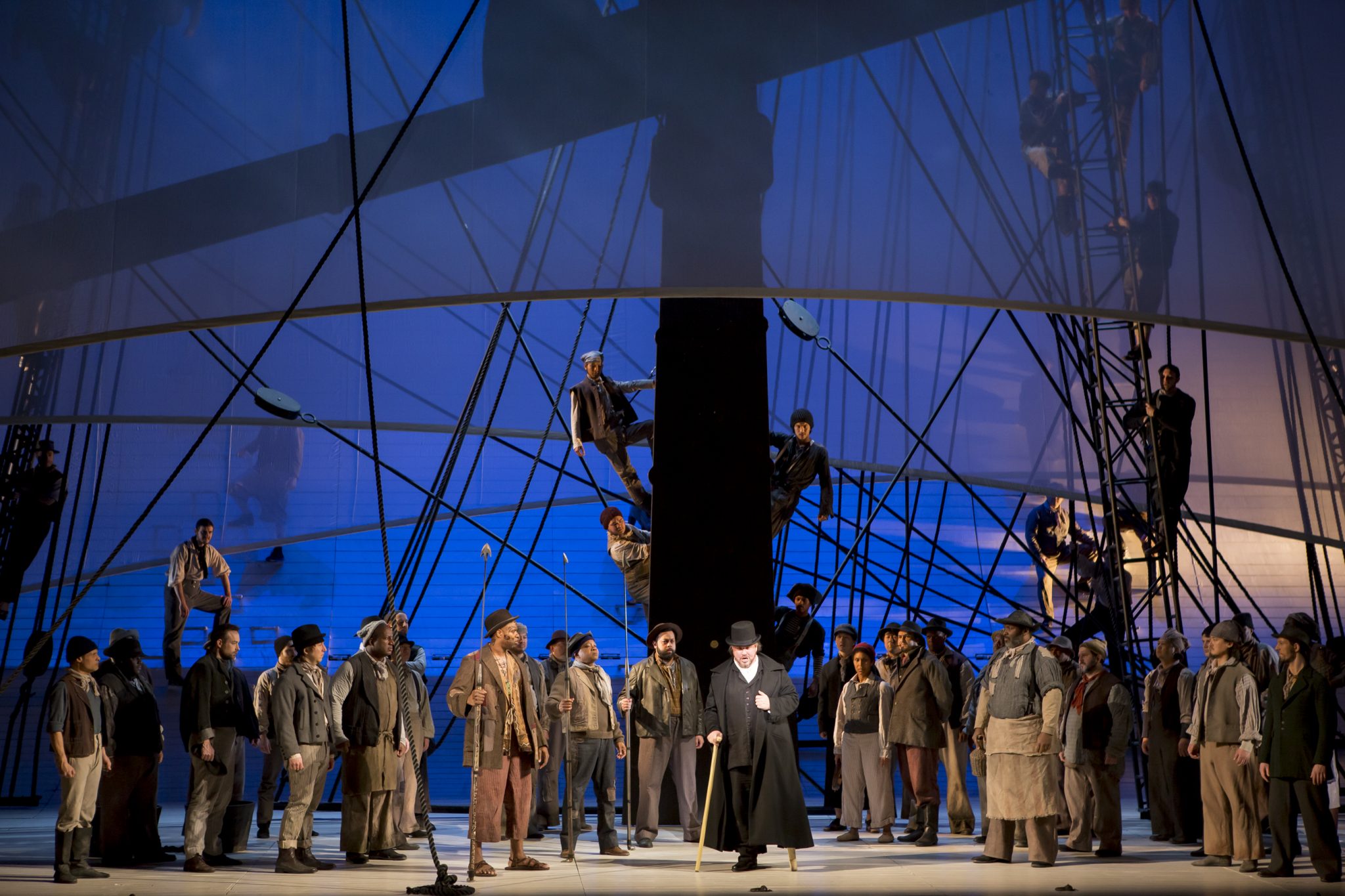

It is not just the Ahab/Starbuck relationship that makes this opera so powerful. The humanity comes from all of the characters interacting on the Pequod. Stephen Costello as Greenhorn shines from top to bottom with his clarion voice. Costello constructs such believable friendships and caring tenderness for Queequeg, sung magnificently by American baritone Eric Greene, and Pip, performed by American soprano Talise Trevigne. Costello’s depth of character knowledge is impeccably during his duet with Greene when Queequeg acknowledges that he is dying. Heggie never acquiesces to quotations but there are definite homages to Verdi-like swells and even Baroque florid vocal style in solo passages. Worth, Costello, and Trevigne made the most use out of their vocal flexibility. The male chorus, under the preparation of Steven Gathman, was a particularly strong vocal element to this production. It was arresting to experience the full wall of sound that emanated during their declaration of loyalty to Ahab before their final, fatal pursuit of Moby Dick.

The feast for the eyes was due to the unbelievable work of Robert Brill, Set Designer; Keturah Stickann, Movement Director and Choreographer; Jane Greenwood, Costume Designer; Gavan Swift, Lighting Designer; and finally Elaine J. McCarthy, Projection Designer. I have quite literally never seen anything like it on the Kennedy Opera House stage. Washington National Opera audiences are blessed to see this production after it has been mounted by five other companies. There are so many moving parts to the stage action and set and nothing seemed out-of-place during Saturday night’s performance. The singers and supernumeraries cover every inch of stage space both horizontal and vertical. The projections were cinematic quality that helped the opera achieve modern excellence. The way they used the projections to create the whaling crew boats was surprising and innovative.

It would be easy to fall into the same blind ambition that Ahab suffered when creating and mounting this opera. Heggie, Scheer, Washington National Opera, the musicians, and the production team found a way to provide the full bravado necessary without falling victim to ego. Like the book, the opera is about so much more than the search for Moby Dick. They all seemed to understand, it isn’t about ‘seeing’ the whale. It is about building the tension and telling each character’s transformational story. There are only five more opportunities to see this performance at Washington National Opera. Tickets and more information are available on the Washington National Opera: Moby-Dick website.