"Ein Fragment muss gleich einem kleinen Kunstwerke von der umgebenden Welt ganz abgesondert und in sich selbst vollendet sein wie ein Igel." - Friedrich Schlegel from Athenaeum¹

[A fragment should be like a little work of art, complete in itself and separated from the rest of the universe like a hedgehog.]

A fragment is not simply just a short piece. It must be a splinter of the larger work that lives in relation to all the other slivers preceding and following it. György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragments op. 24 exhibits hints of the traditional song cycle. As in lieder, the vocalist has a heightened commitment to the German poetry/text while the violin takes the place of the traditional piano accompaniment. The violin, similarly to Schubert’s piano in “Die schöne Müllerin (Op. 25, D. 795), is its own character exposing different emotions which color the spoken thoughts in the vocal line. Kurtág’s compositional style is the ebb away from song cycle writing like Schubert’s. However, the highly stylized text from a single author is the flow back to the traditional form. So who are these men, Kafka and Kurtág, whose words and music have created this challenging and substantial concert work which Martha Morrison Muehleisen (violin), Karen Yasinsky (animator, video artist), and I are performing in January at the Atlas in D.C.?

A fragment is not simply just a short piece. It must be a splinter of the larger work that lives in relation to all the other slivers preceding and following it. György Kurtág’s Kafka Fragments op. 24 exhibits hints of the traditional song cycle. As in lieder, the vocalist has a heightened commitment to the German poetry/text while the violin takes the place of the traditional piano accompaniment. The violin, similarly to Schubert’s piano in “Die schöne Müllerin (Op. 25, D. 795), is its own character exposing different emotions which color the spoken thoughts in the vocal line. Kurtág’s compositional style is the ebb away from song cycle writing like Schubert’s. However, the highly stylized text from a single author is the flow back to the traditional form. So who are these men, Kafka and Kurtág, whose words and music have created this challenging and substantial concert work which Martha Morrison Muehleisen (violin), Karen Yasinsky (animator, video artist), and I are performing in January at the Atlas in D.C.?

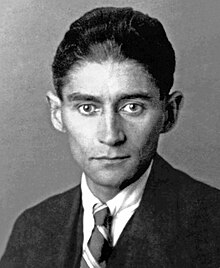

Who is Franz Kafka?

Born in 1883, Franz Kafka has become a readily recognized name due to his enormous impact on Western art and literature. The Czech-born German novelist was raised in Prague and went to law school. After completing school, he worked for a law office and insurance company while writing in his scant spare time. Around 1907 he contracted tuberculosis and moved around to live in various health facilities.

The central experience of Kafka’s life, it seems, was a manifold alienation—as a speaker of German in a Czech city, as a Jew among German and Czech Gentiles in a period of ardent nationalism, as a man full of doubts and an unquenched thirst for faith among conventional “liberal” Jews, as a born writer among people with business interests, as a sick man among the healthy, and as a timid and neurasthenic lover in exacting erotic relationships. ²

Growing up with a tyrannical father and his later inability to sustain healthy romantic relationships seemed to have led to a natural disposition to write about man’s search for identity. Kafka’s main characters are often on a hero’s journey in which they must surmount multiple obstacles to reach their goal and their identities are revealed in contrast to the situations along the way. It is his ability to delineate the loneliness and estrangement of the individual in an uncaring world that makes his short fiction stand out in its time. In fact, it is also this ability that has morphed Kafka’s name from proper noun to proper adjective — ‘Kafkaesque’ — in the lexicon.

Kafka’s writing was in itself fragmentary. He relied on unemphatic and concise language – which aligned itself with the rise of absurdist genres popular in Prague and Vienna. It is this cutting-to-the-quick nature of Kafka’s writing that Kurtág explores musically in Kafka Fragments.

Who is György Kurtág?

Born in February 1926, less than two years after Kafka’s death in June 1924, György Kurtág has risen to be a leader in European classical music. As mentioned last week, his music is not as well-known in the United States but not for its lack of high quality, integrity, and refinement. Significantly, he is the only composer with international recognition that has survived Hungary’s communist regime during the time from 1949–1989. Béla Bartók was an early and important influence on Kurtág who received recognition first as a pianist, having taken lessons from the age of 5, especially when playing Bartók’s works. During those years before he moved to Paris, music from the West was quite limited. It was his time in Paris that allowed him to explore more works by composers such as Webern while continuing his affection for Bartók’s music.

It is interesting to note that Kurtág became well-known as a répétiteur, coaching singers and instrumentalists at the Bartók Music School as well as Hungary’s National Philharmonia, before his work as a composer was spotlighted. One of the reasons that his musical works may not be as well-known in the States could be that he writes with extreme care and great effort. At the age of 59 in 1985, his output had only increased to opus 23 – with some of his works being unfinished or withdrawn for revision. When he composed opus 24, Kafka-Fragmente, in 1985 it became his “longest grouping of aphoristic pieces into a defined ‘whole’” yet.³

Kurtág has an intimate understanding of the voice and explores its limits in many of his works. It is this intimate understanding, obviously born from years as a vocal coach, that makes his writing in Kafka Fragments difficult but never impossible. There is an inherent need and struggle to communicate in his vocal compositions that make them challenging but attractive to performers and audience alike.

Who is the Audience for Kafka Fragments?

Simply? You.

Challenging music or art is not meant to be spiteful or to make you feel stupid. This type of art recognizes, like Kafka recognized, the world can be desolate, alienating, and destructive at times. But, this composition and its performances show that we are not alone with that understanding of the human experience. You, our audience, are experience seekers. You don’t always need to be spoon-fed a story but rather appreciate being shepherded through a performance. An audience for Kafka Fragments values devotion to unique performances. Therefore, I hope you will join us in January for what we are working very hard to make a unique and valuable performance to share with you.

Do you agree? Disagree? Are you our audience? Join us on Facebook. Tweet me @mezzoihnen or use the hashtag #KafkaFrag when sharing these posts.

____

References

¹Hyde, Martha. “Paradoxical Forms: Kafka, Kurtág and the Twentieth-Century Musical Fragment” Journal of the Kafka Society of America 2004: 29.

²Encyclopedia of Philosophy Ed. Donald M. Borchert. Vol. 5. 2nd ed. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006. p5-6. COPYRIGHT 2006 Gale, Cengage Learning

³Rachel Beckles Willson. “Kurtág, György.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 15 Nov. 2013. <http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/15695>.

Related articles

- kafka-fragmente: Telling a Historical Fiction through Chamber Music (sybariticsinger.com)

[…] kafka-fragmente: A Fragment is Like a Hedgehog (sybariticsinger.com) […]