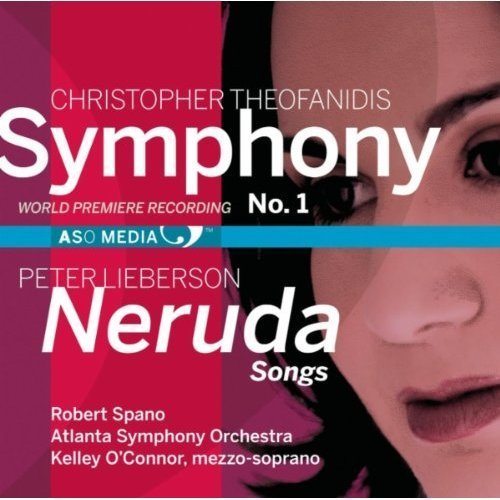

The amazing women over at Operagasm recently asked me to review a new recording of Lieberson’s “Neruda Songs” by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra featuring Kelly O’Connor, mezzo-soprano. I ripped open the package and delighted to see that the disc boasted the world première recording of Christopher Theofanidis‘ Symphony No. 1 in addition to Lieberson’s celebrated piece. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra performs these two 21st Century works with great poise, balance, and authority. It was a joy to spend the day listening to this recording.

Christopher Theofanidis – Symphony No. 1

There is an exquisite balance in the writing of Christopher Theofanidis. The first and fourth movements of Symphony No. 1 are the significant pillars of the work. A joyful woodwind motive opens the movement and carries into other voices as the piece continues. The woodwinds seemingly call out to the rest of the orchestra to join, and as they do, a celebratory daybreak sound emerges. However, the character also begins to shift. This jubilant wind sound gives way to a denser texture as the lower instruments murmur a slightly ominous tone. This new sound oscillates between the lively energetic feeling from the beginning and the portentous new atmosphere. As the first movement nears its closing, the music teeters keenly on the edge of being out of control – while never fully tipping over the brink.

If the first movement was an aural depiction of the sunrise, the second movement clearly takes place in a “nocturnal” sound world. Theofanidis deftly scores the percussion effects using woodblocks and claves to imply a lullaby of nature sounds. This movement is definitely not a typical slow and soft second movement. (Interestingly, the orchestra itself is called on to vocalize on neutral syllables in this movement adding depth and color to the sound.) Theofanidis plays with sound direction in the second movement as he juxtaposes the falling (or “raining” as he calls them) motives and the primary rising, swelling melody. A softened exuberance still lingers from the first movement. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra string players’ nuanced musicianship is on full display here and the third movement. The “scherzo-ritornello” third movement takes the audience for a fleeting ride with the strings darting to and fro. As the strings scurry about, the brass and percussion surge to the front of the sound.

There is an unusual candor apparent in Theofanidis’ ability to uphold the simple intricacies in each movement, especially the fourth, instead of relying solely on the “wall of sound.” To be sure, there are many moments of tremendous sound and expansive harmonies. However, it is how he leads to and leaves those moments that reveal that exquisite balance in Theofanidis’ writing for the symphony. The fourth movement is the doppelgänger of the first, similar to each other but opposite. Wherein the first movement is mostly joyful and dance-like, the fourth is threatening and, at times, unsettling. There are brilliant flashes of lovely consonance, recollections of the first movement, that suddenly return to the snarling, rumbling sounds of the contrabassoon, string basses, timpani, and trombones. Demonstrating that ability to let the intricate sounds stand out, Theofanidis closes the work with fading pulsations leaving the listener in an eerie silence.

Peter Lieberson – Neruda Songs

I have had a love affair with Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs for as long as I have known of them. Who among us music devotees has not savored the story of the composer, Peter Lieberson (1946-2011), setting the famous poetry of Chilean writer, Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), for his wife, the inimitable mezzo-soprano, Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson (1954-2006)? In a commentary for the Neruda Songs Lieberson wrote, “I am so grateful for Neruda’s beautiful poetry, for although these poems were written to another, when I set them I was speaking directly to my own beloved, Lorraine.” With such a story behind the work, it is understandable that a performance by any one else may seem less than. However, Ms. O’Connor has become a sort of torch-bearer for the songs and had fostered a special relationship with their composer after her compelling first performance of the work with the Chicago Symphony.

Neruda’s poetry in Cien sonetos de amor, the collection that holds these texts, is strongly influenced by the transfiguration of the soul through human love. The text is rife with nature imagery and although it does not use much repetition, it does involve many lists. Lieberson is masterful in his understanding of prosody. Using his own repetitions of the text to emphasize certain emotions, especially the return of each love theme, he elongates certain phrases and uses the lists as fuel to reach the next extended emotional phrase. Both first and second movements are perfect examples of this concept. The first poem “Si no fuera progue tus ojos tienen color de luna…” languishes in the third verse on the words “oh, bienamada” (oh, my dearest) and uses the list: “la arena, el tiempo, el árbol de la lluvia” (sand, time, the tree of rain) to speed its return to the loving “oh, bienamada.” The invocation of nature’s elements in the second poem, “Amor, amor las nubes a la torre del cielo…” is felt quite strongly in the wave-like rhythms in the strings.

Lieberson shows his skill in nuance and subtlety with the third movement (Largo): “No estés lejos de mí un solo dia…” (Don’t go far off, not even for a day.) He provides a glimpse at the heartbreaking sentiment just under the surface without coddling the listener. O’Connor follows his inclination in the way she delicates gives meaning to each reiteration of the plea. The anguish and fear of separation is present and raw without being immature.

One of the most effective parts of Neruda Songs is the Hispanic ambiance that the work achieves without being disingenuous. It has the style without the stereotype – both in its composition and in its performance by O’Connor and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. IV. “Ya eres mía. Reposa con tu sueño en mi sueño.” is a perfect example of their ability to take the emotion of both the vocal and orchestral line to the threshold of being excessive and then showing restraint. For example, the portamento in Spanish vocal music has almost become a caricature in itself, but O’Connor uses it stylishly in this movement to highlight the underlying emotions of passion and repose.

Finally the fifth movement, “Amor mío, si muero y tú no mueres…” (My love, if you die and I don’t -) shows the concentrated sensitivity between O’Connor and the ASO. The instruments rise and fall with care to the vocal line – buoying the voice at the most intense moments and giving solitary space to certain moments. The sound the orchestra sets up before “no hay extension como la que vivimos” (no expanse is greater than where we live) is extraordinary and only rivaled by the way O’Connor’s last repetition of “amor” melts into the sound of the orchestra’s last chord.

Lieberson’s commentary from the liner notes also read, “Still, Neruda reminds one that love has not ended. In truth there is no real death to love nor even a birth: ‘It is like a long river, only changing lands, and changing lips.’” With this beautiful recording dedicated to Lieberson’s memory, a depiction of that love continues to live on. Neruda Songs are an important part of our American vocal music tradition. O’Connor and the ASO perform the work with devotion to the original while yet making a recording that stands alone in emotional quality and superb technical skill.

Related articles

- Alex Ross: Remembering the composer Peter Lieberson and his masterwork, “Neruda Songs.” (newyorker.com)

- ASO Moves from Strength to Strength (the-unmutual.blogspot.com)